DiffInE—A Clinical Tool to Promote Diagnostic Reasoning

Vince WinklerPrins, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Georgetown University; Robin DeMuth, MD, Julie Phillips, MD, MPH, Department of Family Medicine, Michigan State University; Dianne Wagner, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Michigan State University

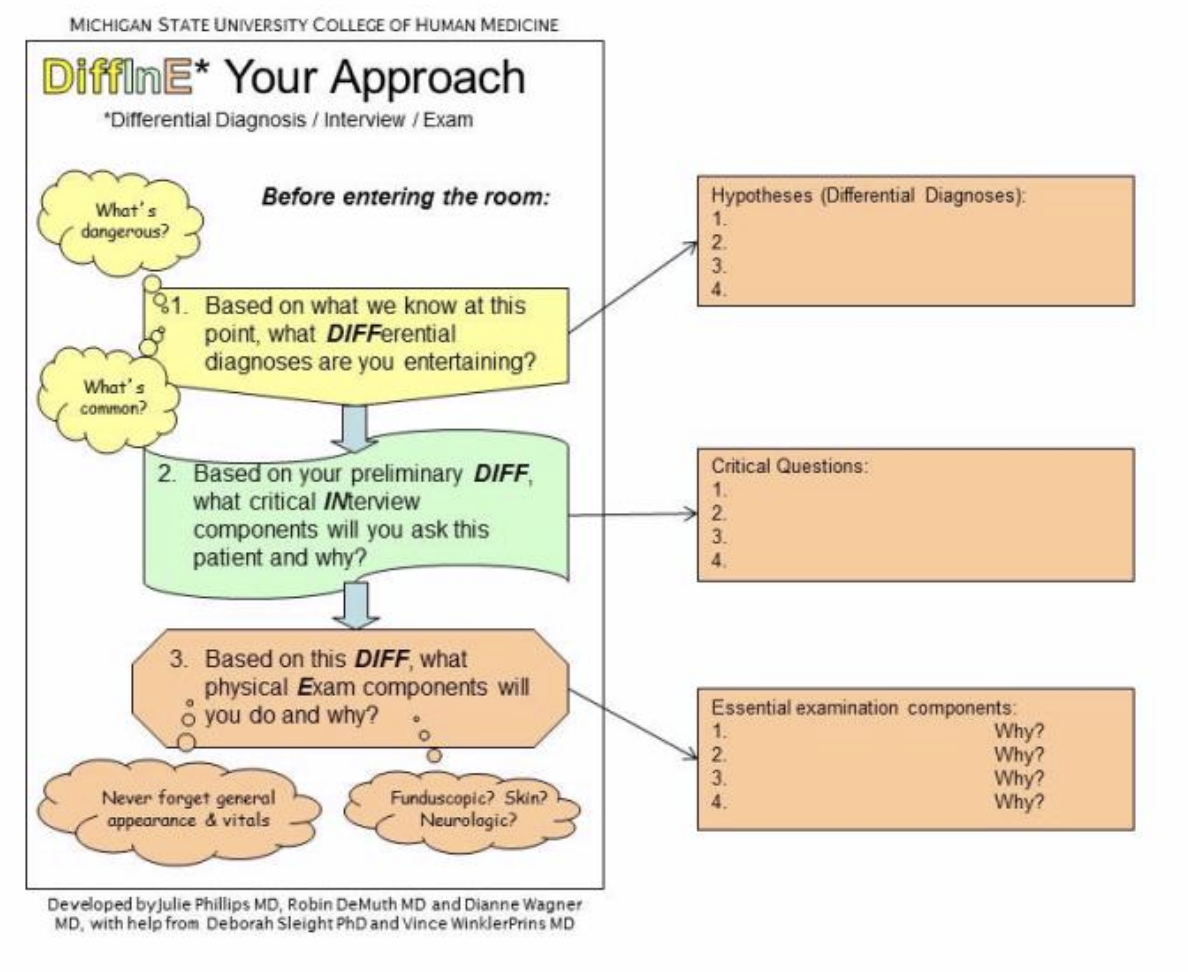

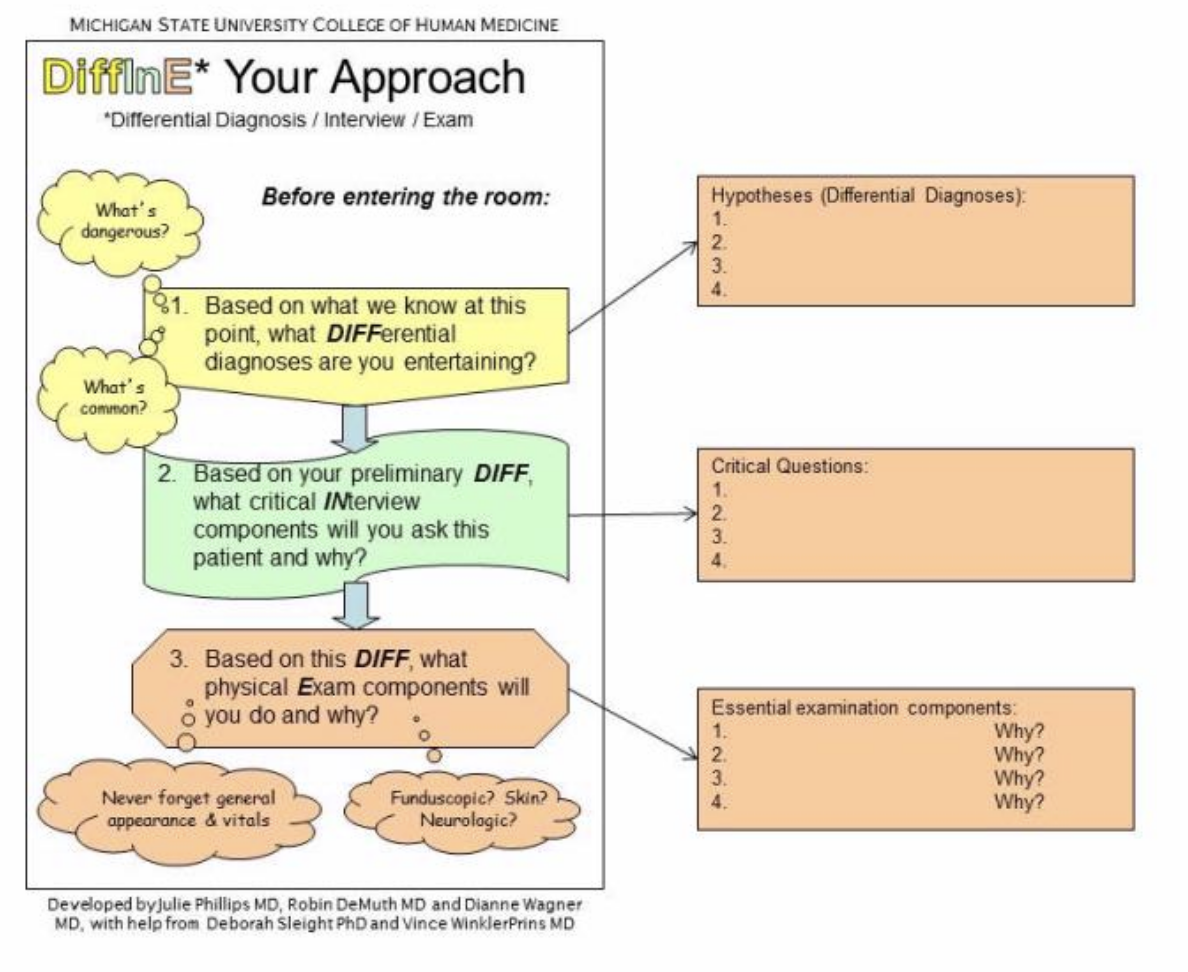

Medical schools spend considerable effort and time teaching first- and second-year medical students the clinical skills they need to be successful in their careers. As students begin their clinical years, however, the majority of their clinical skills training are not done explicitly but by observation of the residents and attending physicians with whom they work. Most students pick up on this intuitively and understand the differences between the explicit methodology by which they learn their clinical skills in the first few years and the intuitive, pattern recognition strategies used by busy practicing physicians. But sometimes they don't. In response to efforts at remediating students who had failed a "must pass" end of third-year series of clinical skill exams (OSCEs), educators at Michigan State University's College of Human Medicine developed a tool to help students make the transition to becoming clinicians by making the process of data gathering explicit and grounded in hypothesis testing. This strategy was initially called SNAP and is now called DiffInE (Differential Diagnosis/Interview/Exam).

DiffInE describes an approach to a problem-oriented patient visit that begins with the chief complaint and is focused on the student answering this question: "What history and physical examination data will you not leave the room without?" From the chief complaint and a brief review of the patient's chart the student should be able to develop a series of hypotheses or differential diagnoses before even walking into the room. These can be listed. From this list a series of critical questions should be considered that need to be asked of the patient and a list of essential examination components that need to be completed. This approach is illustrated below:

Use this tool before the student sees the patient. This will force the student to begin planning for the encounter. Early medical learners will need considerable assistance from us with this step or with novel clinical presentations but as students become more skilled, this should require less time.

This approach makes explicit the diagnostic reasoning process that students need to consider to be skilled clinicians. It can be used by learners and teachers alike and has been used by preceptors in working with students in many clinical disciplines. We urge you to try it as well. A video that discusses the history of the development of this tool and using it effectively is here: http://humanmedicine.msu.edu/cwa/resources/diffine.php.

References

1. Cunningham AS, Bladd SD, Fuller PG, Weinberger HL. The Art of Precepting: Socrates or Aunt Millie? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153(2):114-6.

2. Irby DM, Wilkerson L. Teaching when time is limited. BMJ 2008;336:384-7.

3. DeMuth RH, Phillips JP, Wagner DP. Michigan State University. Teaching students to think like doctors. Presented at the 2010 Association of American Medical Colleges annual meeting, Washington DC.