Immerse Yourself in the Cuban Health System

Participants will spend 6 nights in Havana (Sunday through Friday nights in hotel)

The program is designed specifically to meet the interests of STFM members. Travelers will participate in a full-time schedule of activities and have many opportunities to meet Cubans in their work and home settings.

The week will include a variety of site visits, exchanges, and activities such as:

- Visits to Consultorios (neighborhood family doctor-nurse offices),

- Policlínicos (multi-service secondary-level clinics), hospitals, sites related to maternal-infant and elder health, and a rural community in Havana’s outskirts to understand Cuba’s primary, secondary, and tertiary health care delivery sites;

- Exchanges with members of community organizations and cultural/arts projects promoting health for Cubans of all ages;

- Visits with local experts to historic and cultural landmarks in and near Havana; and much more!

- An expert from the Cuban National School of Public Health (ENSAP) will accompany the group, along with a specialized medical interpreter, a bilingual guide, and a dedicated driver.

Participants will spend 6 nights in Havana (Sunday through Friday nights in hotel).

All travelers’ passports must be valid through 7/25/2020. The exchange is limited to 30 participants; some space will be available for spouses/partners/accompanying travelers, who must participate in the scheduled program due to US travel regulations. Travel and the required academic visa arrangements are made through Marazul, an agency specialized in Cuba travel.

Cost is estimated at $3,500-$4,000 per person, based on the number of participants, final program, and room occupancy chosen. Estimate includes breakfast, most lunches, and international airfare from Miami; it does not include domestic airfare to Miami (US departure point), dinners, tips, and personal expenses. A $500 deposit is due upon acceptance to the program.

Marazul will invoice participants for the final costs 4-6 weeks before departure, and, along with MEDICC, will guide participants on visa and flight arrangements.

Travel Insurance

- EsiCuba/Asistur insurance included with each plane ticket which includes $7,000 coverage for “repatriation” – in case of accident or illness the MEDICC Representative or other in-country staff would accompany the traveler to Cira Garcia Hospital in Havana for treatment, covered by the Asistur policy. Some hotels also have an in-house doctor.

- MEDICC carries an AIG policy (death, dismemberment, accident) that covers all of our travelers. Coverage for emergency evacuation is up to $250,000, and the aggregate limit on the policy is $1,500,000.

- Marazul Charters also recommends Allianz or Travel Guard for additional optional travel insurance.

Complete online application. A $500 deposit per traveler is due upon acceptance to the program.

The application is open June 1, 2019 and close October 1, 2019.

Applications will be accepted on a first-come, first-served basis. A limited number of spots may be available for spouses/partners, who, due to visa requirements, must participate in the full schedule of scheduled activities during the week.

Obtaining an academic visa to Cuba requires careful attention to documentary requirements and the timeline. Trip participants must fully cooperate with deadlines communicated by MEDICC or Marazul in order to meet the deadlines and be able to participate.

A Different Model—Medical Care in Cuba

Edward W. Campion, MD, and Stephen Morrissey, PhD

N Engl J Med 2013; 368:297-299.

DOI:10.1056/NEJMp1215226

The Curious Case of Cuba

C. William Keck, MD, MPH, and Gail A. Reed, MS

American Journal of Public Health 102, no. 8 (August 1, 2012): pp. e13-e22.

DOI:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300822

Cuba’s Focus on Preventive Medicine Pays Off

Sam Loewenberg

The Lancet, Vol 387 January 23, 2016

Field Notes: What Cuba Can Teach Us about Building a Culture of Health

Maryjoan Ladden, Susan Mende

Culture of Health Blog, Jan 29, 2015

Why African-American Doctors Are Choosing to Study Medicine in Cuba

Anakwa Dwamena

The NewYorker, June 6, 2018

A Look Inside Cuba's Family Clinics

Bill Frist

Forbes, Oct 7, 2015

How Cubans Live as Long as Americans at a Tenth of the Cost

James Hamblin

The Atlantic, Nov 29, 2016

Cuba: Where Primary Care Is All About Community

Podcast

Commonwealth Fund

June 28, 2019

Why Cuba? Lessons From an Unlikely Land

This winter, from January 19-25, 2020, STFM is going to Cuba. Aside from the mystique that surrounds this small “forbidden” island nation just off the Florida coast, why go to Cuba?

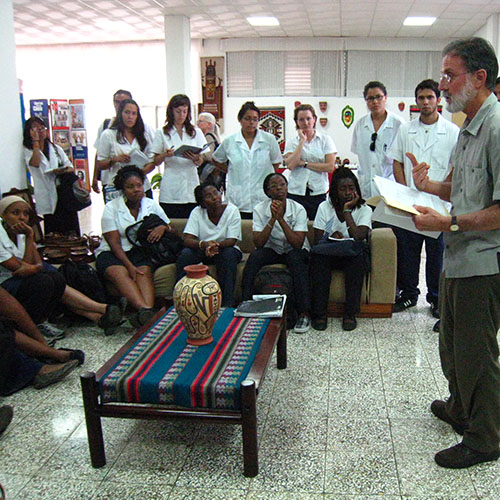

About a decade ago, quite serendipitously, I first heard about what was described to me then as the remarkable health care achievements in this mysterious, somewhat poverty-stricken place; a country that, in my head back then, was stuck in time and had little to offer us in the United States other than sentimentality for old cars and cigars. Rather, I learned how Cuba had created a system that transformed their health outcomes from that of developing nation level in the 1960s, to one with health measures comparable to the United States, all at a fraction of the cost compared to the United States. They did this built around a system emphasizing family doctors and prevention. And, further, they had created an international medical school for non-Cubans, “ELAM” (Escuela Latinoamericana de Medicina or the Latin American Medical School) in Havana, where more than 100 US citizens were studying medicine along with thousands of other young people, mostly from developing countries from around the world – all at no cost to themselves, and based on just the expectation that they return to their home and serve as physicians in communities with a need. I was intrigued.

Now, several trips later, and much more knowledgeable, I remain intrigued and convinced that we have much we can learn from the Cubans and apply here, especially in resource-poor parts of our country.

My education about Cuba has been significantly impacted by getting to know several American ELAM students and graduates who have lived the experience of Cuban health care and medical education. These students are different from the typical cohort of US medical students: most are URM including those from disadvantaged backgrounds, fluent in Spanish, predominantly women, disproportionately interested in Family Medicine careers, and admirably committed to the principals of patient-centered, community- and population-oriented health care.

Dr. Tia Tucker is one of those graduates. Now, a family medicine resident in Boston, she writes compellingly about her training, and why STFM members will be interested in visiting Cuba.

- Rick Streiffer, MD, The University of Alabama, STFM Cuba Trip Planning Committee

An Unexpected Model for Health

An Unexpected Model for Health

- Tia Tucker, MD, MPH, Resident, Tufts University Family Medicine Residency at Cambridge Health Alliance, Boston, MA

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, I was attending Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in New Orleans. There, intending a future medical degree, I tried to envision how to apply my MPH towards rebuilding a city suffering from pre-existing population health care concerns and significant resource shortages. It was through my public health professors that I learned there was a model already in practice, widely recognized for its systematic approach to promoting public health and successful in increasing individual health in the face of limited resources - Cuba. What’s more, I could learn this approach myself as a medical student were I to enroll at ELAM in Havana.

What I learned/What’s so special: The Cubans have created a health care model based on the understanding that the delivery of health care could be improved using a biopsychosocial lens and by having the political will to make healthcare available for all people. They have made tremendous headway in the last decades, and their population no longer suffers from the illnesses and conditions that you are likely to see in countries with a similar GDP. On the contrary, Cubans are recognized throughout Latin America for their health care, while their citizens boast similar life expectancy and maternal/child health stats comparable, even superior, to the US. The developing world conditions are largely gone as Cubans now face the same “first world” illnesses as do our patients.

There was a lot to learn from the Cuban model. First, the education at ELAM is free, based only on the expectation that students commit to returning home to practice in underserved areas. I am very thankful for that, which has reinforced the importance of affordable education for those genuinely intending to serve their communities. In the US, even applying to medical school, affording the licensing exams and going through the residency interview processes can be financially inaccessible or create a financial setback for some students. I often wonder why there is not opportunity in the United States that would help committed students curb more of the cost of becoming a licensed physician.

Two predominant clinical lessons shone through in my education. One is that prevention is the key in developing better health outcomes particularly in poor communities. Cuban physicians always think and use “prevention” and “promotion of health” first, in part because of the scarcity of resources and technology, but also due to our training and out of a firm commitment to its value. Second, to achieve better individual health outcomes, we must integrate community and public health approaches into the clinical perspective. In Cuba, everyone has a family doctor who is based within walking distance in a neighborhood clinic, the consultorio. Commonly, the family doctor actually lives there, too. That doctor sees everyone in the family and is required to see everyone in his/her panel, including on home visits, at a frequency based on a health status and risk assessment. The family doctors are also responsible for a neighborhood’s health assessment, and because they live in the neighborhood, they are a part of the community and understand it. The doctor uses a distinct method to quantify risks, disease and sequelae called dispensarización (Moliner & Soberats, 2001). Dispensarización allows the doctor to identify the risk of individual members of a family unit and based on an understanding and formal assessment of the community health, to link the levels of health care and develop strategies.

Why you should go to Cuba: At ELAM, students are told that family physicians are the most important part of healthcare, that we are “an army of white coats” standing between disease and the communities that we work to protect. In fact, all Cuban physicians train to be, then practice first as, a family doctor. A much smaller percentage than in the US later go on to subspecialty training, but retain the lessons and perspective of prevention, community and public health. A high level of respect for family medicine is held at the highest levels of government as well as throughout the population. It is eye-opening and heart warming to see what a system based around the family doctor has been able to achieve.

Since 1997, MEDICC, a 501(c)3 organization, has worked to enhance cooperation among the US, Cuban and global health communities aimed at better health outcomes and equity. MEDICC publishes the MEDLINE-indexed MEDICC Review; organizes educational travel to Cuba for US health professionals; assists US students and graduates of the Latin American Medical School (ELAM) to return to US underserved communities, and organizes Community Partnerships for Health Equity to improve health care and access in US communities.

LEARN MORE