The Vape-Free School Project: An Education Initiative to Address e-Cigarette Use Among High School Youth

Bryan Leyva1; Rashaud Senior1; Alison Riese, MD, MPH1,2; Jordan White, MD, MPH1; Paul George, MD, MHPE1; Patricia J. Flanagan, MD1,2

1The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI;

2Hasbro Children’s Hospital, Providence, RI

Sixteen percent of US high school students in 2015 reported using an e-cigarette in the past 30 days, which is roughly a tenfold increase since 2011 (1.5%).1 In Rhode Island in 2015, 41% of high school students reported ever using an e-cigarette, and 19% reported using an e-cigarette in the past 30 days.2 This is a public health problem, given that e-cigarette use can lead to nicotine addiction and use of more harmful substances such as traditional cigarettes.3 Recently, the US Surgeon General made a call for innovative programs to prevent e-cigarette initiation and discourage continued use.4 To date, few interventions to reduce e-cigarette use among youth are described in the scientific literature.

The Vape-Free School Project is a school and theory-based5 education program to increase knowledge, influence attitudes, and decrease likelihood of using e-cigarettes among teenage youth in the state of Rhode Island. The program consists of a 1-hour interactive workshop for high school students. The workshop was developed by two medical students using input from local health teachers and based on results from in-depth qualitative interviews with ten community key informants.

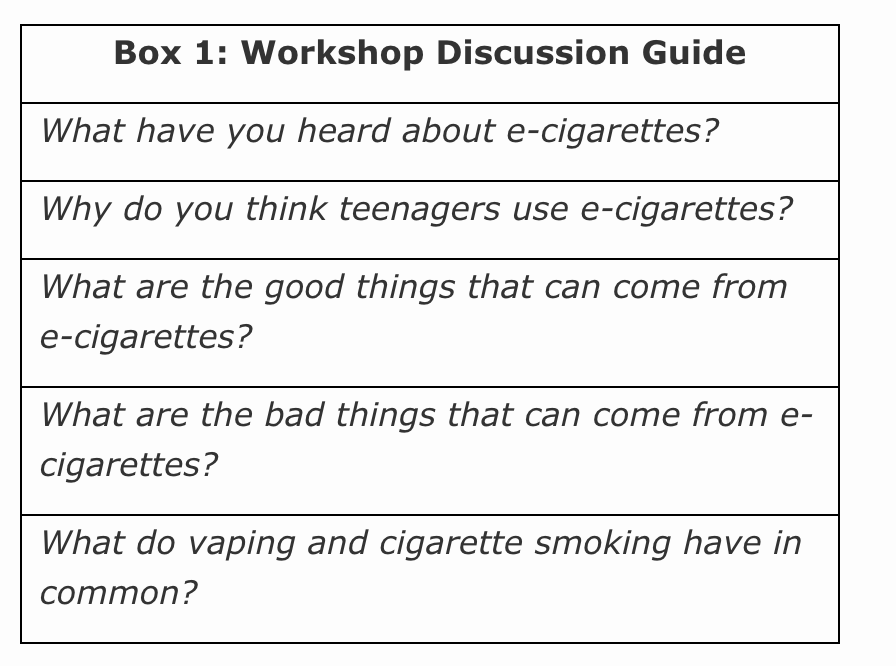

The workshop begins with an introduction to the history of tobacco companies in the United States, and a brief 15-minute review of the health consequences of cigarette smoking. It proceeds with a 30-minute facilitated discussion about e-cigarettes. The facilitator guide is based on principles of motivational interviewing and structured around five broad, open-ended questions (Box 1).

Included in the guide are references to e-cigarettes in pop culture and additional prompts to encourage student participation. The workshop is designed to cover topics such as the dangers of e-cigarette use among teens, the effects of nicotine on the developing brain, the potential harms of second-hand vapor, and key concepts such as dependence, tolerance, and withdrawal. The last 15 minutes of the workshop is intended to provide education around communication, refusal, and other social skills to help youth handle peer pressure. Skills are reinforced through role playing exercises. A feedback survey is given to each student to complete at the end of the workshop.

Program Impact–Preliminary Results

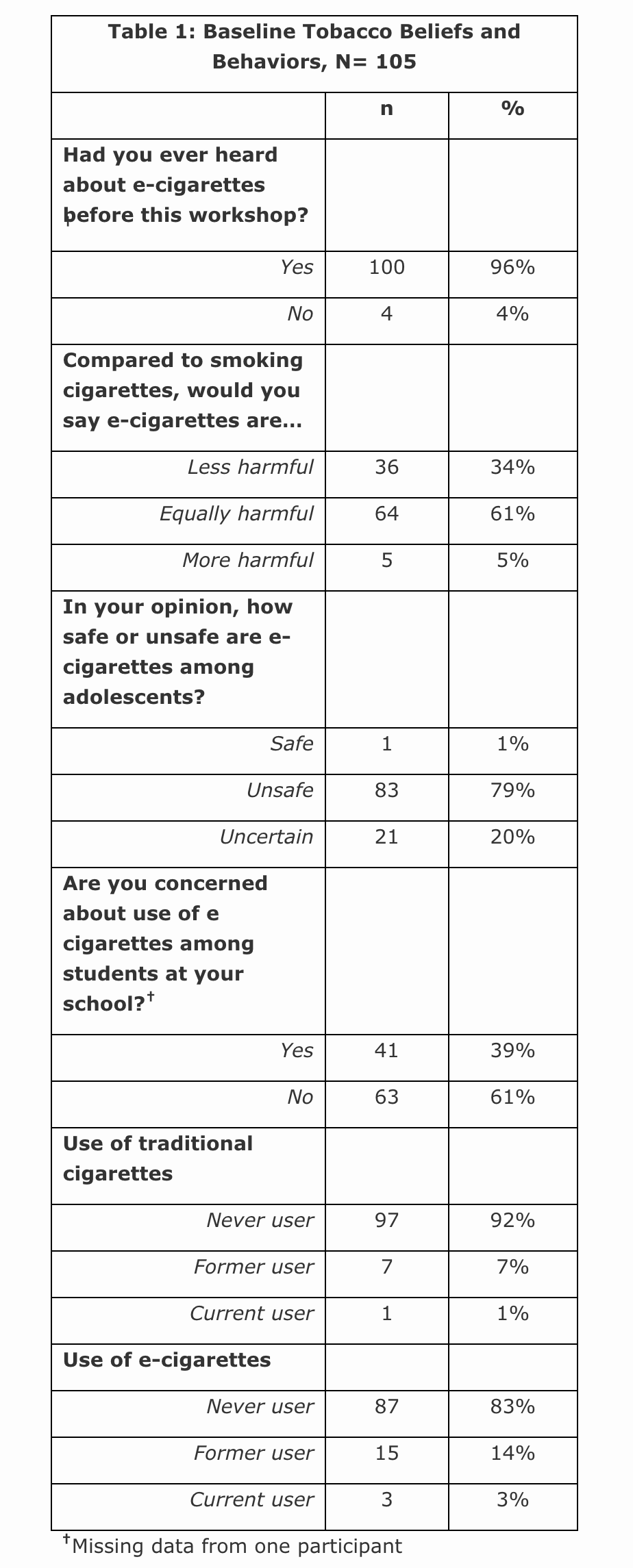

We implemented the intervention workshop in two Providence-area high schools, reaching a total of 105 students through six workshops. Sixty percent of students (n=63) were in tenth grade, and the remaining in ninth grade (n=42). More than half of the students (n=57, 54%) identified as male. The mean age was 15 years. See Table 1 for students’ baseline tobacco beliefs and behaviors.

The overwhelming majority of students (98%, n=103) reported feeling more knowledgeable about e-cigarettes after the workshop. Fifty-six percent of students (n=58) indicated that their attitudes towards e-cigarettes had become less favorable, while 38% (n=40) reported their attitudes did not change. Among the students who reported no change in attitudes, 82% (n=33) indicated e-cigarettes were unsafe and 90% (n=36) had never used an e-cigarette. Nearly all students (98%, n=99) reported they were less likely to use e-cigarettes in the future as a result of the workshop. Furthermore, most students agreed that they “enjoyed the workshop,” that “the material was presented in an organized manner,” and that they “would recommend the workshop to other students.”

Teachers were also highly satisfied. One teacher stated, “the class was highly engaged and interested in the topic, the information was accurate and presented in a way to encourage questions and maximize participation.” Another commented, “the information provided was able to empower students with facts and dispel many of the myths that students believe to be true about these products. The students seemed to be hanging on every word of the workshop facilitators. I was very glad my students were able to participate.”

Just the Beginning

Our preliminary results suggest that a brief school-based workshop can improve students’ knowledge and attitudes about e-cigarettes, and reduce their likelihood of using these products in the future. We are motivated by health teachers’ receptivity to partnering with medical students, and the immediate impact this project had on students as well as our own education as future health care providers. In the upcoming months, we will seek to establish partnerships with additional schools, and involve more medical students in this effort.

References

1. Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(14):361-367. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a1.

2. 2016 Rhode Island Kids Count Factbook. Providence, RI: Rhode Island KIDS COUNT; 2016.

3. Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA. 2015;314(7):700-707. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.8950.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General—executive summary. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2016.

5. Montano DE, Kasprzyk D. Theory of reasoned action, Theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, eds. Health behavior: theory, research and practice, 5th Edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2015:95-124.